"A Fire-Bell in the Night," Part II

The Further Development of Christian Nationalism in America

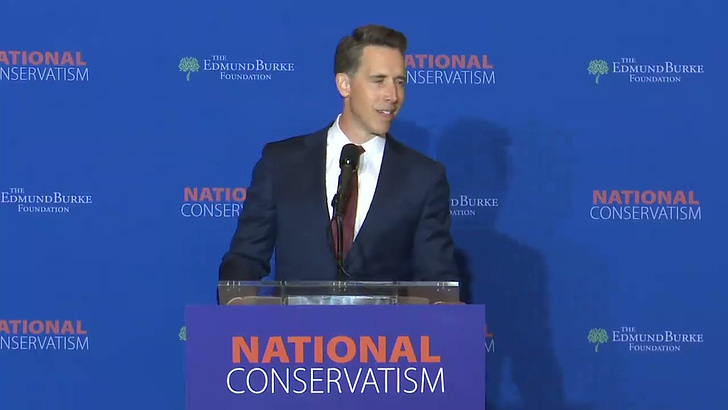

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) received a fair bit of attention for this startling part of a speech delivered to a gathering of “National Conservatives” in July 2024, but his assertion that the U.S. was founded on explicitly Christian theological and political principles is nothing new. American Christians from across the denominational spectrum have made this claim from time to time throughout our nation’s history, and it is not hard to find evidence to support at least the idea that this was so: sessions of Congress open with a prayer, most often delivered by a Christian clergyman, “In God We Trust” is emblazoned on our currency and chiseled into the marble of some of our federal and state government buildings, and our politicians frequently invoke the God of Abraham in their speeches. As I noted in Part I, no politician in this country can expect to get elected if they don’t profess not just a belief in God, but can show proof that they attend a church or synagogue at least semi-regularly. Muslim politicians have a rockier road to elected office, but a handful have managed it, and atheists have an even more difficult time.1

That Hawley and, well before him, Reps. Marjorie Taylor-Green (R-Georgia) and Lauren Boebert (R-Colorado) have praised Christian nationalism and argued that the First Amendment does not establish any “wall of separation” between Church and State proves that what was once a quietly held conviction among a substantial proportion of Protestant evangelicals and adjacent Republican politicians has become more of a mainstream political conviction. It has arisen more aggressively in response to pushback from liberals, some Democrats and Progressives, as well as a handful of evangelicals who truly understand the dangers of demolishing the Wall of Separation. Nevertheless, Christian Nationalism has grown in popularity and influence over the last few decades, and accelerated substantially since the Election of 2016. My previous post described the origins of the movement as a sort of presumption that Christianity makes one a good person, and that good government means having good people (understood as men in the early modern period, of course) in positions of political authority. However, with the rise and triumph of premillenarian eschatology among the Millerites and the popularity of Harriet Livermore, Christian nationalism became increasingly, and inextricably, entwined with premillennialism.

The degree to which American society came together in support of the war against the Axis Powers in World War II did not long survive the Potsdam Conference. There was certainly a broad agreement that the Soviet Union posed a significant threat to the United States when the Russians developed their own nuclear weapons, and once the Communist revolution in China had established a coherent government and supported the North Korean attempt to impose that revolution on the entire peninsula that began the Korean War in 1950, anti-Communism was the only glue holding the nation together politically. It was harnessed by white conservatives and evangelicals—there being substantial overlap between those two groups—to oppose the African-American civil rights movement, even as a more liberal (though certainly not seriously progressive) ethos moved the U.S. a little more to the left. However, while we would be right to celebrate the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) that began the process of desegregating public schools, an argument could be made that white conservatives could see this as a strategy to, as Vito Corleone would say, “keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.” In other words, African-American schools could become factories churning out civil rights activists, while putting black kids in white-majority schools run primarily by white teachers and administrators would militate against education on behalf of social justice.

Nevertheless, 1954-55 marks a significant turning point in American politics, as opposition to the Democratic Party’s gradual move to the left during the Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, and the Brown decision, led to the Republican Party’s lurch toward the right. William F. Buckley, Jr. founded the National Review magazine devoted to conservative ideology, while Robert W. Welch, Jr. founded the still more fascist-adjacent John Birch Society in 1958. White evangelical Protestants formed the vanguard of this massive political realignment, as southern Democrats gradually became Republicans, essentially on the grounds of opposing civil rights—albeit without sufficient strength to block passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965).2 Again, it can be argued that President Johnson’s support for civil rights was more of an attempt to weaken the Southern Christian Leadership Conference led by Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, than an expression of his own belief in social justice. Certainly the F.B.I. continued to surveil King and other civil rights activists throughout the period, alleging covert Communist involvement. Avowed and incipient Christian nationalists decried the overall liberalization of American society in the 1960s, and began to mythologize a pre-Brown America, which has come down to the present day in the lionization of the “Greatest Generation.”

The conservative revolution that began in the 1950s gained considerable momentum in the late 1960s, and appeals to the United States’ Christian identity were an integral part of the campaign to delegitimize and constrain Johnson’s “Great Society” programs. Johnson predicted that the civil rights acts would cost Democrats the South, and he was right. Conservative Democrats who had not yet jumped ship to the Republican Party steadily undermined Johnson’s plans for reelection in 1968, while the quagmire that was the Vietnam War further eroded the president’s political ability. He declined to seek his party’s nomination, and Republican senator Richard M. Nixon easily won the Election of 1968. Although raised in a Quaker household, Nixon had actively curried support from evangelicals and employed a racist “Southern Strategy” to rally white conservatives and suppress black voter turnout. However, Nixon’s support for the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and legislation to ensure clean(er) air and water brought some criticism from the right, though not enough to compromise what turned out to be a landslide reelection in 1972. The Watergate scandal ended in Nixon’s resignation in 1974, and Vice President Gerald R. Ford was considered too liberal by a Republican leadership that became increasingly interested in former California governor Ronald Reagan, Barry Goldwater’s hyperconservative ideas being a bit too unpalatable by the majority of American voters—though certainly not to Christian nationalists. Rev. Billy Graham, who had become the best known preacher in and beyond the United States since the 1960s, had parlayed his fame to worm himself into the halls of power, hobnobbing with senators, congressmen, governors, and ultimately to becoming an unofficial spiritual advisor to Nixon, Ford, and Carter through the 1970s. Although not explicitly a Christian nationalist, Graham nevertheless equated being a good Christian with being a good American—meaning that one had to hate Communism, celebrate capitalist economics, and embrace socially conservative politics. Thus he was implicitly a Christian nationalist.3

As described in Part I, Christian nationalism incorporated the Darbyite theology of dispensationalism, which divides human history into seven dispensations that linchpinned Cyrus Scofield’s famous “Study Bible” that became the standard King James Version of The Bible for most evangelicals. It was the basic schema William Miller adapted to his reading of the prophetic books of the Old Testament, and helped propel premillenalist theology to the forefront of evangelical theology.

Whereas the Seventh-Day Adventist Church that grew out of the Millerite movement eventually abandoned date-setting, dispensationalism has proven too irresistable to those who try to match up historical and current events to charts like the one above and later modified versions of it in order to predict exactly when the events described in the Book of Revelation will take place. It became more widely popular when aspects of dispensationalism were explained in Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth (1972) to argue that the Rapture and the Second Coming were near at hand on account of rampant socio-political liberalism, environmental degradation, and global strife.

Jimmy Carter, the Democratic nominee for president in 1976, should have effectively split the evangelical Christian vote, given his religious bona fides, but American Christianity—especially in its evangelical expressions—had drifted far away from its core emphases upon charity and compassion. Rather, it had drunk so deeply from the vats of capitalism and postwar jingoism that to the evangelical mind, to be Christian is to be American, and to be American is to be an (evangelical Protestant) Christian. Many American clergymen began preaching a gospel that not only celebrated the United States as God’s Elect Nation, but suggested that true faith brings personal prosperity, much as America’s religiosity was responsible for its rise and triumph as a global superpower. Prosperity Gospel theology had long been a fringe movement since the 1920s, but it became increasingly prevalent in the 1960s and ‘70s, and gaining broad popularity through the debut of such television shows as The 700 Club (est. 1966) and The PTL Club (1974). Some evangelicals did support Carter’s candidacy—enough to weaken Ford’s bid for election—but it was the absence of southern support that doomed Ford. Carter’s being a popular governor of Georgia, as well as his centrist orientation, handed him a narrow victory.

To some extent the Republicans saw the Carter Administration as an opportunity to reorient themselves around a more conservative agenda, and it was in the late 1970s that Christian nationalists entered the mainstream of Republican politics. Televangelists echoed and amplified an increasingly politicized Protestant Christianity, exemplified in the careers of Pat Robertson, host of The 700 Club and founder of the Christian Broadcast Network in 1960, as well as Oral Roberts, who founded Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1963. Another influential evangelical was James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family in 1977 and the Family Research Council in 1981 to propagate conservative religio-political values in strict opposition to the Gay Rights Movement as well as the Equal Rights Amendment. The most influential evangelical outside of Billy Graham, however, was Rev. Jerry Falwell, host of The Old Time Gospel Hour and founder in 1979 of the “Moral Majority”—an organization operating as a political action committee. Between them, Graham, Roberts, Falwell, Dobson and Robertson—who never worked together as a group, it should be emphasized—contributed to a trend toward the American public taking for granted that the United States was founded by Christians as a Christian nation. In 1988 Robertson embodied these beliefs when he mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the Republican presidential nomination, while Rev. Jesse Jackson’s campaign for the Democratic nomination that same year incidentally reinforced these notions.4

Ronald Reagan’s handy victory over Carter in 1980 was not just a victory for the Republican Party, but a victory for Christian nationalism. He had the endorsement of the Moral Majority and spoke at events organized by Christian nationalist groups throughout his eight years in the White House, in addition to hosting all of them there at various times. The Southern Baptist Convention likewise endorsed Reagan, who supported its political activism throughout the 1980s, and helped to turn the SBC in a more overtly Christian nationalist direction. Evangelical Protestant influence on the Reagan Administration was embodied in his first Interior Secretary, James G. Watt, who justified his efforts to weaken the Environmental Protection Agency, open up protected lands to fossil fuel extraction, and deregulate heavy industry on the grounds that God has ultimate sovereignty over the Earth, and not human beings. In any case, he stated his belief that “I do not know how many future generations we can count on before the Lord returns,” and that the Earth’s natural resources are supposed to be exploited as part of God’s command to exert dominion over the world. Most evangelicals agreed, claiming that Earth’s finite resources could not be exhausted before The End, and that pollution was not really a problem since it must be part of God’s plan. So toxic had the blending of conservative Republican political philosophy with radical evangelicalism become that Canadian author Margaret Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), a cautionary work of speculative fiction imagining a Christian nationalist takeover of the U.S. that would eliminate women’s rights and reduce women to scrupulously subservient, faithful wives and broodmares.5

Reagan’s Vice President, George H. W. Bush, easily won the Election of 1988 essentially by promising that his administration would be a virtual continuation of Reagan’s, and there is a persistent allegation that he once declared that atheists should not be considered American citizens—an allegation that comes from a single biased source and cannot be verified. In any case, Bush did less to court evangelical support, major leaders among whom did not have the degree of White House access they had enjoyed under his predecessor. His militant stance against Communism did help him maintain evangelical support, and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was perceived as a victory for American Christianity and its entwining with democratic-republican ideology. The Democratic Party found itself drifting slowly to the right, embracing an ideology of “neoliberalism” that eschewed New Deal and Great Society progressivism in favor of a “pragmatic” centrism. The election of Bill Clinton in 1992 was not the setback to the Republican Party that some Republicans at the time thought it to be, and Newt Gingrich (R-GA), Speaker of the House, nevertheless moved the G.O.P. further to the right in response, pulling the Democrats still further along the center in a rightward direction. Conservative evangelicalism gained considerable strength in the wake of the Clinton election, as did charismatic non-denominational Protestantism, which became unabashedly politicized.6

Conspiracy theories about the Clintons arose during the Election of 1992, and gained significant strength during the Waco Debacle in 1993, when a compound full of Branch Davidians, a radical offshoot of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, was raided by the FBI and the BATF on suspicion that they were stockpiling firearms, as well as allegations of child abuse. The Branch Davidians’ leader at the time of the raid, Vernon Howell, suffered from delusions of messianic grandeur and renamed himself “David Koresh,” and almost certainly abused his power to marry several young women—at least a few of whom were young teenagers—and preach the imminent Apocalypse for which they prepared by weapons training for the War of Armageddon. When efforts to enforce a search warrant were met with resistance, the federal government responded with an overwhelming show of force that the besieged Branch Davidians interpreted as the beginning of The End. The siege was expected to end in a general surrender, and while some managed to escape, most remained inside the main building that somehow caught fire, exploding gas containers inside that destroyed the building and left dozens dead. The government absolutely mishandled the situation, handing the Branch Davidians the apocalypse that they believed was about to unfold. A somewhat similiar situation involving Randy Weaver, an implicit Christian nationalist, in Idaho the previous year raised suspicions among radical Christian nationalists that the federal government was godless and anti-Christian, and the disaster in Waco simply confirmed them.7

The bombing of the Alfred P. Murrough Federal Building in Oklahoma City in April 1995 was, according to the bombing’s architects, retribution for Ruby Ridge and Waco, though they were serving an agenda that was more in line with the vague anti-government militia movement’s, rather than any overt Christian nationalist one. The groups operating in Michigan, Idaho, and Texas, among other areas, seemed determined merely to overthrow liberalism and impose a sort of fascist dictatorship, though none of them had a coherent ideology, much less a viable plan to carry out a coup. Through the later 1990s and 2000s, Christian nationalism remained a fringe element of conservative American evangelicalism, and characterized in the press as a lunatic fringe at that. But while the wild-eyed fanatics attracted most of the scant attention paid to Christian nationalism, the clear-eyed tacticians continued to incorporate, carefully and surreptitiously, the smaller aspects of their beliefs into the public consciousness and mainstream political tenets. Nobody with influence over public opinion pushed back against incessant assertions that the United States is a Christian nation founded explicitly on Protestant Christian principles, despite historians and sociologists who published books and articles struggling to refute them.

The next installment will address the more recent history, and ultimate triumph, of Christian nationalism, and how the second Trump Administration will attempt to realize—albeit despite Trump’s ignorance of how he is being used—Christian nationalist plans.

The 118th Congress of the U.S. has just one member who is “out” as a Secular Humanist—Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.)—while one other, Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.), labels herself as unaffiliated (https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2023/01/03/faith-on-the-hill-2023/). As of this writing, seven state constitutions (Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, N. Carolina, S. Carolina, Tennessee, Texas) explicitly bar atheists from holding public office, though the ban is unenforceable and cannot withstand legal challenges. That being the case, then why haven’t these states amended their constitutions?

Bryan Hardin Thrift, “Jesse Helms’s Politics of Pious Incitement: Race, Conservatism, and Southern Realignment in the 1950s,” The Journal of Southern History 74 (Nov. 2008), 887-926.

Curtis J. Evans, “A Politics of Conversion: Billy Graham’s Political and Social Vision” in Andrew Finstuen, Grant Wacker, and Anne Blue Wills, eds., Billy Graham: American Pilgrim (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Elizabeth Dias, “How Pat Robertson Created the Religious Right’s Model for Political Power,” The New York Times, 8 Jun. 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/08/us/pat-robertson-religious-right-politics.html. Robertson won four state primaries, for a total of just over 9% of the vote. Jackson performed far better, winning nine state primaries with a total of just over 29% of the vote.

Daniel Williams, God’s Own Party: The Making of the Religious Right (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), chap. 9; Bill Prochnau, “The Watt Controversy,” The Washington Post, 30 Jun. 1981.

The Monica Lewinsky scandal had a lot to do with the Republicans’ ability to pull a quite moderate Clinton in their direction. See Steven M. Gillon, The Pact: Bill Clinton, Newt Gingrich, and the Rivalry that Defined a Generation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Dennis B. Downey, “Domestic Terrorism: The Enemy Within,” Current History 99 (Apr. 2000), 169-173; Stuart A. Wright, “A Decade after Waco: Reassessing Crisis Negotiations at Mount Carmel in Light of New Government Disclosures,” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 7 (Nov. 2003), 101-110.